My Chunida

He seemed born to blend. Unwittingly he bridged the divide

between bangal (east bengalee) and ghoti (west bengalee) in an exemplary

manner. His presence led to rapport between the cricketers and the footballers

of Bengal. He possessed a magical mass appeal that gave him unprecedented

popularity among the populace. His popularity even in the non-television era of

his time would have dwarfed many a current cinema star.

Born and brought up in the liberated Murapara zamindary (now

in Bangladesh), my maternal link, where he was preceded by Sarojini Nayudu, Bhanu

Bandyopadhyay and Nripati Chattopadhyay, the young Chuni utilized his sports talents

in the path of reconciliation of differences between the two artificially

divided parts of Bengal.

Destiny too willed so. While he was showing off his undoubted

football skills to his Tirthapati Institution friends at Deshopriyo Park, a

distant pair of eyes watched with awe and wonder. Walked across, asked him his

father’s address and by evening was knocking at the door. The elder Goswami

instantly recognized the boxer-footballer Bolai Chatterjee and was too happy to

allow his son to be at the Mohun Bagan ground the following morning for a

practice session. As the cliché goes…the rest is history.

Former players were wide-eyed in amazement to see the talent

exhibited by the child prodigy. Within the course of the year he was the

shining star of the club and state teams. By 1958 at the age of 20 he was

scoring goals for India.

Under Syed Rahim’s coaching he flowered beside the

magnificent duo of PK Banerjee and

Balaram and held India‘s flag high at the 1960 Rome Olympics. He went a step

further at the 1962 Jakarta Asian Games when India won the gold under his

leadership. This was best-ever era of Indian football. The most successful

period when men of the calibre of Arun

Ghosh, Jarnail Singh, Peter Thangaraj, Simon Sunder Raj, Mario Kempiah and

Yousuf Khan among a host of others dominated the Asian football scenario. Apart

from PK and Balaram, the evergreen glamour of CG stood out in the glittering panorama.

Chuni Goswami led India in the pre-Olympic qualifying match

at Calcutta’s Rabindra Sarovar Stadium in 1964. As a 14 year old enthusiast, I

remember attending the 1-month camp every single day as a spectator.

Unfortunately the brilliant Rahim was replaced by an English coach named

Wright. Chunida scored the lone goal as India lost 1-3 to Iran with my

favourite defender Arun Ghosh denying the opposition a dozen goals. Never again

was India good enough to qualify for Olympic football.

Lack of guidance held him back from accepting a foreign

assignment with Tottenham Hotspur in his heydays of 1960s. This was a typical

scenario in our football context. While cricketers were going abroad and taking

up assignments in the English cricket leagues, our football players never

received any encouragement from our ‘frog in the well’ administrators, who were

content with their clubs’ politics, personal prominence and media flatterers.

Thankfully Chuni Goswami had the talent to seek other avenues.

He was deeply attached to cricket since his school days. He

represented Monoharpukur Milan Samity at cricket while a student at Ashutosh

College. He also represented Calcutta University at cricket while doing wonders

and winning championships on the football ground.

Chuni Goswami made his Ranji Trophy debut under the strangest

of circumstances. At the peak of his football career he was selected to play

against Jaisimha’s Hyderabad in the Ranji Trophy semi final. The year was 1962-63

the season when four West Indies fast bowlers came to India. Roy Gilchrist the

fearsome fast bowler held little terror for the debutant as he most

courageously gave support to this skipper Pankaj Roy who scored two hundreds in

the match. Thereafter he played very irregularly for Bengal as he was busy with

his football commitments for club, state and country.

In the Ranji final against Bombay in 1968-69 he played two

glorious knocks of 96 and 84 displaying his leanings for cross-batted strokes,

particularly the sweep. His fantastic speed between wickets is still in the

memory of people who have seen him bat. Chunida’s lone first-class century came

against Bihar at Jamadoba in 1971-72 when he promoted himself to bat at number

3.

The highlight of his cricket life was of course the fantastic

victory of Central-East Zone combined team under Hanumant Singh which inflicted

the 1967 West Indies team to an innings defeat at Indore. Chunida took 5 and 3

wickets and in tandem with Subroto Guha had the powerful Caribbeans on the mat.

Skipper Wes Hall top-edged a high skier towards mid wicket. Goswami ran almost

30 yards from mid-on, lunged forward to hold the one-handed and then actually

went on a victory lap around the ground! Skipper Hanumant’s cultured voice,

“Chuni, we are not playing football” was drowned by the thousands who had come

to see their soccer hero playing cricket. That was the kind of popularity and

affection he enjoyed.

In 1971-72 the Bengal cricket captaincy crown was on his head

and he led Bengal to the final. The following year – my debut season – he led

Bengal for the last time and announced his retirement. This idea of when to

call it a day is a splendid example that he has set for others. At 34 he

realized another few years of cricket would be a waste of time as he would be

curtailing the prospect of a deserving youngster. He had left international

football at 26 and now first-class cricket at 34. A master-stroke: a great

lesson for most sportsmen.

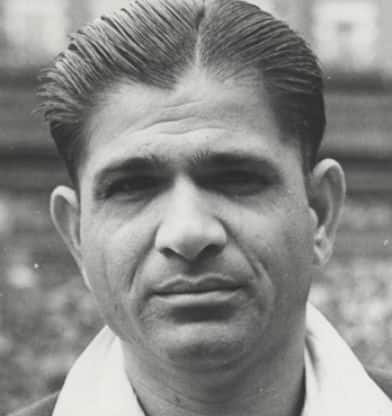

If Subimal was his first name, surely his middle name was

Flambuoyance. Both the names were destined to stay in the background. Glamour

and Chuni Goswami became synonymous. Reeking of glamour, Goswami was a

revelation in a world of introvert Indian sportsmen. Most of our champion

sportsmen in the pre 1960s were quiet, confident men who avoided controversies

and publicity. Not so Goswami. He reveled in his extrovert form. He loved

crowds, companionship and constant media coverage.

To my generation of sports lovers, Chuni Goswami was a

magical name. Handsome of bearing, glamorous of manner the man had a distinct

individuality. Smiling, waving, chatting he seemed to be in perpetual motion.

Extrovert to the extreme, he brought the Bengal cricketers out of their shells.

With Chunida as captain the Bengal team learnt to take on the opposition

eyeball to eyeball. Within the typical easy-going exterior of Bengal team

mates, he planted a tough approach to the job, which obviously did wonders for

the state in the future. This was a

distinct contribution of his.

He seemed destined to bond people. Following independence and

partition the differences between the Padma migrants and the Bhagirathi

residents were distinct and definite. Hilsa

and Chingri. Bangal and Ghoti. Only

the Mir Jafar’s sat on the fence as far as loyalties were concerned. In such a

precarious scenario emerged a young lad with eastern Bengal tastes and lingo to

become the hero of the western Bengal bhadrolok.

Without meaning to do so, his approach and actions actually assisted to bridge

the yawning chasm between two extremely strong loyalties. So popular was he

that I remember praying with all earnestness: Let Chuni Goswami do well but

East Bengal win! I am sure there were many school boys of the 1960s with

similar prayers.

***

A long association of about 60 years has come to an end. Our

childhood hero is no more. Chundai has left the maidan for the Elysian Field.

The last time I met

him was on his 82nd birthday at his Jodhpur Park residence on 15

January this year. The Philatelic Bureau issued a stamp in his honour that day.

The ever-jovial face was in distinct discomfort. To enliven him I recounted to

him of his own glorious days; his magnificent contributions; his unique brand

of witticisms. A tear or two welled up as he smiled his enjoyment. But no words

emanated from the brilliant raconteur. Sad sight; sadder still to relate.

Really unfortunate.

For an extrovert like

Subimal Goswami, universally popular as Chuni, to be sofa-tied and tongue-tied

was indeed a dungeon-like existence. Boudi, Bubli, his wife and Chunida’s

endearing grandson gave him the best of companionship possible but the

inevitable was near at hand. Though extremely saddening, perhaps his ‘passing-away’

was, in a sense, a blessing in disguise. No one would have liked to see his

ever-cheerful face in that posture.

***

My elder brother Deb was a regular opener for Bengal and

Mohun Bagan in the early 1960s and so I was quite a frequent visitor to those

matches. Saw Chunida often enough and was thrilled to get his cheery smiles.

Once he offered me and my friend Bapi toast and tea at the Mohun Bagan canteen

when we were waiting for a lift from Deb. That year I also attended his wedding

reception as the guest of his elder brother Manikda, who played club cricket

with me at Milan Samity at the time.

However the first genuine meeting was in December 1967 when I

attended the Mohun Bagan net after writing my final school exams. With Chunida

and his very witty elder brother Manikda around, the net sessions were full of

laughter and humour, repartees and wise-cracks. Chunida warmed me up with, “Oh!

No, another Mukherji. Oh! No, another with specs.” I was too stunned to think

of a reply but realized that I had gained acceptance at the Bagan household.

Never before I had met anyone with his peculiar brand of

speech and humour. However I realized that he had a funny peculiar way of

speaking: a statement in the form of a query. Had a fantastic sense of humour.

He would keep us in splits.

“This pitch is a pace bowler’s graveyard.” Before the star pace bowler could take

another breath, the Bengal captain replied, “Please take rest today. I need

soldiers who will fight for his team.”

That was a typical straight forward Chuni Goswami repartee.

He had no time for excuses, vague comments or for the soft-hearted. He himself

led from the front and expected everyone to follow. Chunida did not believe in

unnecessary theories. He always maintained that if you cannot motivate

yourself, no one can motivate you. Absolutely to the point.

Once he admonished a prominent batter, who complained about

the size of the sight-screen after being dismissed, “Watch the ball and forget

the sight-screen? Did you get sight-screens in school, college and road-side

matches?” He gave cent per cent and more

to the cause and expected others to do so.

He received accolades and recognition from every possible

platform. Arjuna award was followed by the Padma Shree. A whole lot of honorary

posts were created for him. Influential people queued up to shake his hands and

be photographed.

But the main accolade came from the common man on the road.

His popularity in the days before television coverage was miraculous in the

extreme. People stopped their cars to wish him. People at airports and railway

stations stared at him and waved. Once our train was held up for more than 2

minutes at Bardhaman till Chunida came to the door of the train coach to wave

at the multitude waiting to catch a glimpse of the man they had only heard of and

read about.

To my generation, Chuni Goswami was all glamour and skill.

Every movement of his we would try to copy. The way he walked, the way he

spoke, the way he smiled. Our childhood hero was far ahead of the celluloid

stars in sheer popular mass appeal. Always impeccably dressed, he spoke in an

easy manner, mixed easily and genuinely enjoyed companionship.

He possessed a very rare sense of timing. He knew what to do

and when. He knew when to retire just as he knew when to take up a new

assignment. He knew his abilities just as he knew his limitations. His life has

been a shining example to many. He never wanted to be a teacher but his life

was a document of teaching.

Not only was he my first Bengal captain, he was also the man

who released my first book Cricket in

India: Origin and Heroes in 2004. Ten years later he penned a fabulous

Foreword to my second book Eden Gardens:

Legend and Romance. About three years ago, in a wistful mood one evening

Chunida said, “I want you to write my obituary.”

“Ki bolchen ta ki?” (“What are you saying?”) I protested.

In a serious vein, he just added, “I am your captain. I am

your senior. I like the way you write.”

His companionship was full of humour and nostalgia; prawn and

beer. I am indeed blessed to have had him as my captain.