Royalty at two extremities

Indian cricket is replete with strange happenings. A legendary cricketer

who had no time for Indian cricket received the highest accolades possible. At

the other extreme, two average-ability players who sacrificed their self-interest

for India’s cause kept receiving taunts throughout their lives and beyond.

Irony at its height. Contradictions following contradictions. Yes, that in a

nut-shell is Indian cricket.

*******

Ranji’s

Strange Behaviour

Ranji never played a Christian

stroke in his life. So said Neville Cardus. True it was. The Indian prince’s

batsmanship had all the charms of Oriental mysticism. The bat was his wand as

he mesmerized England, both spectators and oppositions, with his wristy

elegance.

At a time when the top batters

would play the ball mainly to the off-side as the ‘Champion’ WG Grace would do

with his customary mastery, the graceful, lissome figure of the Indian prince

would gently caress the ball from outside the off-stump to the untenanted areas

on the leg-side. It was magical.

How did he do it with a

perpendicular-held bat? With a cross bat, we understand. But how with a bat

held straight? He was the first to use the pace of the ball to glance it

between the fine-leg and square-leg regions. The fluidity of his steely wrists

gave the art of batsmanship a new dimension.

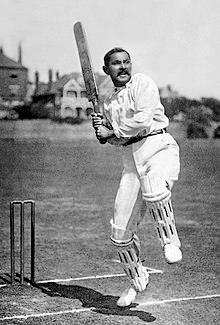

Mustachioed and ebony of

complexion, the traits of his race were distinctly apparent in this conjuror’s

every step. Medium of height, shining black hair thinning on the temples the

man looked every inch an Oriental. Yet he was giving the white man a lesson in

effortless stroke execution at the white man’s own sport. Who is he? What are

his antecedents? How is he lighting up our grey skies with his golden streak?

These were the queries in the minds of cricket followers from Yorkshire to

Sussex.

Kumar Shri Ranjitsinhji was the

adopted son of the Raja of Nawanagar, who had no male heir to his throne.

Following the best possible education on offer in India, Ranji went to England

for further studies with his school headmaster in tow. Cambridge was the

university chosen.

The climate and the food disagreed

with the prince brought up in India. He was overwhelmed by the liberal western

culture that he daily encountered. Perplexed he was by the differences. After

the initial hiccups, he however found his métier in the game of cricket. He had

played a little at school in India but in England in the game of cricket he

found an ideal escape route from the dreary routine of academic life.

His soft features belied his

determination. He spent hours practicing at the nets. The young prince went for

the trials of the Cambridge University cricket team. But he returned

disappointed as players of far superior ability got the nod ahead of him. He

realized that he would have to work really hard if he wanted to be in the first

XI. And that is exactly what he did.

He appointed professional coaches,

who would bowl to him for hours against payment. Never tried to copy WG Grace

or Arthur Shrewsbury, the role models at the time. Very sensibly he developed a

distinctive style of his own. He did not go for power; he went for precision.

He used his wrists more than he used his forearms. While others tried to play

on the off side, he preferred to play on the leg side. He picked up the tenets

of back-foot play from WG but avoided the cross-batted shots.

In the 1890s Ranji would organize

his net sessions in such a manner that the professional bowlers would have the

incentive to further their gains. Apart from their usual fees for bowling to

Ranji at the nets, they would get a shilling every time they hit his stump.

Ranji had the brilliant idea of putting a coin on the top of each stump! Later

many have claimed to have done so, even in their bio-pics, but Ranji was certainly the pioneer of this

novel idea.

Ranji’s mastery was quickly fathomed, selected

for Cambridge University, invited to play for Sussex and finally for England in

the Manchester Test in 1896 against Australia. He began his Test career with a

century for England against Australia. He sent spectators and the journalists

into raptures. They were amazed to see the man’s effortless mastery over pace

and spin. No conditions would upset him. No opposition would overawe him.

He was majestic in whatever he did.

He had all the Oriental flavor of mysticism around him. Silk shirt fluttering

in the breeze, he gave the impression of effortless ease. His strokes conveyed

the essence and not the effort. He strode supreme and earned universal

admiration. Ranjitsinhji, who later became the Jamsahib of Nawanagar, was

popularly known as ‘Smith’ during his Cambridge University days.

Unfortunately for Indian cricket,

Ranji had no time for his motherland. He had a very poor opinion of Indian

cricket and Indian cricketers. He played a few matches in India but never

showed any interest in promoting the game here. At Eden Gardens he once played

a match as well as another at Natore Park in the Picnic Garden district of

Ballygunge in south Calcutta. Even the grand exploits on English soil of

Mehellasha Pavri and Palvankar Balloo, who were so highly rated by discerning

British critics, did not quite wake up Ranji from his stupor.

He seemed quite oblivious to the

progress that was happening in India. The quality of Quadrangular cricket

tournament had no appeal for him. He had no praise for Deodhar or for CK

Nayudu. In fact the magnificent all-rounder Amar Singh Ladha was from

Nawanagar, Ranji’s own territory, yet the grand old man never offered even any

words of encouragement to him.

Ranji’s strange conduct in relation to Indian

cricket defied all logic. Why was the great cricketer so adamant in his

opposition to the march of Indian cricket? No one will ever know. Ranji’s

biographer Simon Wilde did not give high marks to Ranji as a person. Actually

he trashed many of the Ranji-related eulogies of the earlier authors.

When Ranjitsinhji’s nephew,

Duleepsinhji – another outstanding batsman – was invited to play for India in

1932, it was reported that Ranji flatly refused to give permission by saying

that Duleep would not play as he was an English Test cricketer!

Yes, Duleepsinhji made his debut for England

against South Africa in 1929 and later scored a century against Australia at

Lord’s the following summer. He could

have easily served his motherland in India’s early days at Test cricket in the

1930s. But he had no desire to defy the dictates of his stern uncle, whom he

obviously idolized.

When the inauguration of the

national cricket championship in India was being discussed at the BCCI meeting,

the Maharaja of Patiala Bhupindra Singh announced that he would donate the

trophy and the trophy would be named after Ranjitsinhji, who had just expired.

Although Ranji had no time for Indian cricket, the magnanimity of Patiala and

the BCCI members of the time need to be acknowledged.

At Calcutta’s Eden Gardens in 1950

a huge concrete block came up, right opposite the pavilion at the time on the

western fringes of the ground. Pankaj Gupta, the evergreen man of Indian

cricket and the dominant personality of National Cricket Club, then the

custodian of the iconic Eden Gardens promptly named the awesome structure

‘Ranji Stadium’. That is how it remained till the so-called modernization

demolished it in the 1980s. Thus the first-ever structure in India to be named

after a sportsman was Ranji’s. This was possible because of the broad vision of

Pankaj Gupta and his committee.

The naming of the trophy for the

premier national championship was indeed a grand gesture to honour the

magnificent batsman who first made the world realize that Indians could master

the British sport. No doubt, Ranji established the name of India on the world

cricket map.

It was also ironical that a man who

never encouraged Indian cricket or Indian cricketers would be given the highest

possible honour. Strange are the ways of Indian cricket. Stranger still was the

conduct of Ranji.

Kumar

Shri Ranjitsinhji remained an enigma till the very end.

Natwarsinhji & Ghanashyamsinhji

Prior to India’s inaugural tour to United Kingdom in 1932 to play her

maiden Test match at Lord’s, the national selectors – HD Kanga, AL Hosie and

Ashan ul Haque – offered the captaincy to Bhupindra Singh, the maharaja of

Patiala. Bhupindra at 41 was well past his prime as a player and moreover

because of pressing duties at Patiala State, he declined the invitation.

In 1932 the Indian cricket team set sail for Britain to play their first-ever

official Test match. Now the replacement captain selected to lead the touring team

was the maharaja of Porbandar, Natwarsinhji. His deputy was the maharaja of

Limbdi, Ghanashyamsinhji.

Both were very average cricketers. At the time, in India in the 1930s, it

was felt that leaders could only come from the princely classes. Hence the two

members of the royal families were given the top two posts in the Indian

cricket team to play their debut Test.

Thankfully both Natwarsinhji and Ghanashyamsinhji were educated, liberal

souls in the most appropriate sense of those words. They were sensible enough

to understand that if they were in the playing XI, the national team would

become weak. Both declined to play in the inaugural Test at Lord’s. That Test

match being the sole Test of the series, they never got to play for India again.

Supreme sacrifices that have gone unacclaimed.

Skipper Natwarsinhji and his deputy Ghanashyamsinhji decided that the

best choice to lead would be the ‘commoner’ CK Nayudu. Accordingly India’s

first-ever Test captain was Cottariya Konkaiya Nayudu, a magnificent

all-rounder and a born leader of men. CK’s elevation to the top was not because

of the selection committee, but because of the magnanimous gesture of two

princely gentlemen.

The chief reasons for highlighting this extraordinary event are quite a

few. To begin with, this particular issue has not yet seen the light of day.

Cricket historians could not decipher the magnitude of the gesture of two men

who sacrificed immortality for the just cause of the nation. Both Natwarsinhji

and Ghanashyamsinhji deserve our salute.

Secondly, in the annals of international Test cricket such a unique

sacrifice has never been seen. No international cricket captain-elect has ever

relinquished his debut captaincy in this magnificent manner. For sheer

magnanimity the acts of these gentlemen should forever be recorded in cricket

history.

Thirdly, this is a very significant issue in the light of modern

thinking. At a time when ‘commoners’ in BCCI are fighting among themselves for

every bit of crumb on the table, we in India have had ‘royal’ people who knew

how to sacrifice self for the cause of the deserving individuals as well as for

the nation.

Natwarsinhji and Ghanashyamsinhji are names that even the top Indian

cricketers and administrators are unaware of. In fact they do not want to know

about them. As one former India captain has recently observed, “…why bother

about what happened earlier; all that is in the past!”

Unfortunately some very uncharitable remarks were printed to denigrate

the average batting skills of these two royal members. It was said that they

owned more cars than they scored runs. This comment was totally uncalled for.

To begin with, they did not select themselves. Secondly and most importantly,

they sacrificed the honour of representing their nation in a Test match.

Instead of praising their magnanimity, we have had people criticizing them!

Today where is the time for chivalry and magnanimity in the quagmire of

corruption? Now the whole emphasis is on

money and power; power and money. Nothing else matters.

Genuine cricket connoisseurs would do well to remember these two

unheralded and forgotten gentlemen of Indian cricket, who sacrificed personal

honour for the benefit of the nation.

*********

Raju!

ReplyDeleteOnce again you have excelled!!

While Maharaja Ranjit Singh is well known to us, but nowhere have I read such a detailed narration of the person. Eccentric no doubt, but nonetheless with steely nerves and unparalleled guts!!

Regarding the other two gentlemen, here again, I knew nothing, repeat nothing about them.

Your writings are a treasure trove!!

Salutes to you!!

As ever,

Ashok

Thanks, Ashok, for the compliments.The contributions of Natwarsinhji and Ghanashyamsinhji have never been raised by our cricket writers.

ReplyDeleteDear Raju Kaka:

ReplyDeleteThe participation of scions of Indian royal families in Indian cricket is a notable aspect of the history of our country.

They played with passion, dedication and interest; possibly, they also did not have to struggle with material support which was and is required in playing cricket ably. Definitely at that era when financial sponsors and support was not easy to come by. That was a strength they possessed. Isn't it?

The three concerned royal personalities seem to have contributed, in their own respective ways, to a colourful chapter of Indian cricket.

Please correct me if I am incorrect. As mentioned before, my opinions are those of an ignoramus in cricket.

With Regards,

Ranajoy

I appreciate your opinions. I value the judgement of people who are free-thinkers. You are certainly one of them. But to be honest with you, talent in any sphere has nothing to do with wealth, poverty or the so-called variety of backgrounds.

ReplyDeleteI am not always ready with my replies but love going through your articles.God bless you, Rano.

on the world cricket map.

ReplyDeleteIt was also ironical that a man who never encouraged Indian cricket or Indian cricketers would be given the highest possible honour. Strange are the ways of Indian cricket. Stranger still was the conduct of Ranji......Good one.