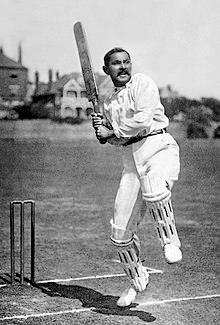

Budhi Kunderan: unorthodoxy at its height. Note the Fred Perry-tee shirt and the watch at Test cricket in the 1960s! With Jaisimha, the only captain who really understood the non-conventional Budhi

Against West Indies in 1967 at

Eden Gardens, Kunderan mis-hooked a Wes Hall bouncer, top-edging the skier to

the 3rd man region! Skipper Gary Sobers from 2nd slip ran

sideways about 60 yards near the boundary rope and got his hands to the ball,

only to drop it.

Only Sobers

could have tried it. None else. It was not a catch by any means. The ball was

in no-man’s land. But the issue here is that the batter Budhi patted his raised

bat to applaud Sobers’ effort. Amazing indeed. This approach set him apart. To Kunderan,

there was little difference between Test and picnic cricket. He loved to be

both a participant and an audience.

We all want to

go back to our primary-school days. No cares, no responsibilities. None to

impress. Simple pleasures of life. Budhi retained that innocence till his last

days. He never really wanted to grow up. He never did. He had the spirit to

continue with the carefree approach of a child. He achieved what we all wished

but were not able to do so.

Unknowingly, because of his

fun-loving approach Budhisagar Krishnappa Kunderan became a cynosure of all

eyes. He had little care for any win-loss result. He was neither a showman nor

a stage artiste. He was born to enjoy the fun of life. As his second name

suggested he was the baby-Gopala adored by all Indians of every hue. Whichever profession he would have chosen, he

would have remained a fun-loving man without any pretensions.

In a sport known for its traditions and

customs, Budhi Kunderan appeared to be a man who had lost his way. He was the

first to change the contours of apparel for cricketers. Cricketers of his time

in the 1960s were so used to flannels, gaberdine and cotswol outfits that we

could not fathom any need for any change of textile. But Budhi, the heretic,

thought otherwise.

In a Test match

he actually batted wearing a collared tee-shirt! It was the Fred Perry-designed

cotton tee, highly popular in the 1960s, even among the non-tennis fraternity.

Wonder if anybody would possess a picture of Budhi in that relaxed tee-shirt. Sport & Pastime of the 1960s

published many such pictures. My full collection of S&P of 1950s and 1960s

got pilfered by a renowned establishment crony, otherwise most surely a tee-shirt

wearing Kunderan action-photo would have appeared in these columns.

Unusual

happenings and Kunderan were rarely away from each other. He played for his

country even before playing first-class cricket! Only a handful have done so. It

was said that so impressed was Lala Amarnath, then a national selector, by

Kunderan’s daredevil antics in inter-railway matches that he decided Budhi was

ready to play Tests! If Lalaji had decided, no one would have dared to raise

his voice in Indian cricket at the time in the late 1950s.

Within months of his Test debut against Australia in 1959-60, he was playing his first first-class match against Jammu & Kashmir. To the statisticians' delight, young Kunderan raced to a double century on debut in a blitzkrieg of an innings.

Our

Gopala, like his namesake, played numerous roles. If he was the child makhan-chor at one moment, he was also

the charioteer who advised Arjun at the battle of Kurukshetra. If he was

dancing on Kalia one moment, then he also had his nails out as Narasimha to

help Prahlad.

So it was with Budhi. For sheer

versatility he has had few equals. He played for India as a specialist

wicket-keeper. He played for India as a specialist middle-order batsman. He

played for India as a specialist opening-batsman.

As if these were not unusual

enough, Kunderan even opened the bowling for India in a Test match in England

where the pitches are, as we all know, highly conducive to pace bowlers. So we

may well presume that Kunderan was selected for that particular Test match to

do the specialist’s job of pace bowling as well! He was an outstanding fielder

as well in the deep: agile, acrobatic, swift.

But even these unusual happenings

lose their significance when we have a look at his most successful series as a

Test cricketer. England, then M.C.C., had come under Mike Smith in the winter

of 1963-64. The first Test was at Corporation Stadium, Madras. Prior to the

start of the opening day’s play, the players were warming up and Budhi

Kunderan, one of the reserves, was helping out at one of the nets.

About twenty minutes before the

toss, the first-choice wicket-keeper, Farokh Engineer, was writhing in pain

having suffered a nasty injury to his finger while warming-up. The selectors

had no option but to ask Kunderan to be ready to replace him. Within minutes

not only was Budhi playing, he was actually putting on his pads to open the

innings for India!

Those days cricketers played in

flannel shirts and in full-sleeves shirts. But Budhi had no time for orthodox mode or

manner. He strutted out in a white, half-sleeved, tight-fitting shirt and tight

drain-pipes! It was considered a sacrilege to wear such an outfit even in

first-class matches at the time. But Budhi was no respecter of persons or

things; or of customs and conventions. Why would our adorable Gopala worry

about the customs of ordinary men?

Next to no time he was Dennis the

Menace in person. He stepped out of his crease to hook David Larter’s bumpers

to the long-leg fence! Went down on his knees and slashed Barry Knight over

cover-point. Began sweeping away-going spin and, to add sauce, drew away to the

leg side to cut square off the top of the bails. It was sheer bravado, if not

outright madness. No normal player would dare to even contemplate such a

display of complete disdain. Especially when he is making a comeback as a late replacement.

Budhi Kunderan went berserk as

did the crowd. Cricket connoisseurs shook their heads in disbelief, but the

spectators loved every moment. Whatever it was, it was certainly not the

cricket as we knew it. It was pure mayhem. Was his attitude not the precursor

to the T20 approach to batting?

England’s much-vaunted

professionalism, ‘scientific’ field-placing, ultra-defensive tactics went

through the window in next to no time. Budhi the heretic had no time for

heritage. The hurricane called Kunderan was in no mood for security or style, convention

or custom. He was at no race. He just wished to highlight gay abandon. No

wonder like Gopala again, he was the ‘darling’ of the masses.

His was an approach against

orthodoxy, against grumpy faces, against theorists. When the hurricane finally

subsided, Kunderan had raced to 192. It was an innings of sheer dare-devilry,

sheer audacity. For sheer belligerence that innings has rarely been bettered.

By then Kunderan had earned crowd

support. They had received their money’s worth. To a man they admired his guts,

his sense of adventure. Medium of height, slight of build he was an unlikely

hero. But the handsome chiseled features of the ebony-complexioned man made

people sit up to take notice. He had taken convention by its throat and put it

to rest in a most audacious manner.

After that attacking near

double-century Budhi became a certainty for the rest of the series. He opened

the batting in his own unconventional way but was extremely consistent, ending

the series with yet another century. He was the highest run-getter as well as

the leader in the batting averages. Not that he cared. Nor did he ever bother

to remember, not even after retirement.

He was a desperado in the best

sense of the term. Being of the attacking mould, he played with fire and took

grave risks, often leading to suicidal dismissals. Security and orthodoxy were

alien concepts to this man. He loved challenges. He embraced risks. He was a

fighter pilot in the garb of an Indian Railway cricketer.

It was this defiant attitude,

this aversion towards convention, this allergy to dull monotony that endeared

him to the cricket lovers. His exciting personality permeated that excitement

among the onlookers. When Kunderan walked out to bat, we did not expect

match-winning innings. Nor did we hope for match-saving graces. We wanted

action; we wanted adventure to lead us to thrills that we did not get in our everyday

life. In this approach Budhi hardly ever failed to disappoint us.

We who were brought up under the

strict discipline of school-regimentation just adored him for his

individuality. We cared two hoots about results. We wanted to be free birds

like he was. We wanted adventure; we wanted to be ourselves. In him we realized

our dreams. When I told him once about it many years later in Aberdeen, his

eyes moistened. He just stared at me. Not a word was exchanged. The feeling and

the tears said it all.

He had come to tell the world that

cricket was only a sport, meant to be enjoyed with full freedom. Everything

about him was unusual. He would not wear loose cricket trousers, but ‘drain-pipes’!

He would open for India with the approach as if he was the no. 11 in the batting

order! He would walk as if he was on a modelling ramp. This is not to be

construed a criticism, but a compliment to his fun-loving, exciting persona,

whom we adored.

In looks he resembled the handsome Rohan Kanhai. In batting too his approach – not the skill: none can match Kanhai’s creativity – matched the world numero uno of the 1960s. If Kanhai was the epitome of individualism in a highly individualistic West Indies side, so was Budhi Kunderan in the India team. In Calcutta we the Bongs adored him for his individualistic streak.

But Budhi’s supposed inconsistency of performance

went against him in selectorial eyes. His batting average of 32 happens to be higher than all his contemporary wicket-keepers, which included PG Joshi, Naren Tamhane, Farokh Engineer and KS Inderjitsinhji. Throughout his career of just 18 Tests in 8 years he was 'on trial'!

Once at Edgbaston in 1967 he

opened India’s bowling attack. When asked by the umpire what he would bowl,

Kunderan replied that he would have to bowl one delivery to find out! And then,

promptly bowled a bumper to Geoff Boycott, who was so taken aback that he had

to duck to avoid it. Yes, that was typical Kunderan, the non-conformist.

He happens to be one of the few

batters who have been called back by the opposing captain after being given

out. This happened in the Mumbai Test against West Indies in 1967 when Lance

Gibbs appealed successfully against him for a catch at short leg by Gary Sobers.

But Sir Gary, the sportsman that

he was, withdrew the appeal and Budhi stayed back. Budhi took the opportunity

to score a brilliant 79 against the deadly combination of Hall and Griffith;

Sobers and Gibbs. This can only happen to cricketers who are genuinely loved by

their opponents. Yes, Budhi was surely one of these rare birds.

Budhi Kunderan made his Test debut against Richie Benaud’s Aussies in 1959 in the 3rd Test at Brabourne Stadium. In the following Test at Chennai he attacked the world-class attack of Davidson, Meckiff and Benaud with a belligerent knock of 71 with strokes which baffled even a captain of Benaud’s class.

Within a year, against Ted Dexter's team, despite taking 3 catches and 2 stumpings in the 1st Test, he had to make way for reasons never convincingly told! Budhi never had any 'backers', so very essential to survive in Indian cricket.

He went on tours to West Indies and England,

but his batting approach did not quite succeed as it did on Indian wickets. Nor

did he get adequate opportunities. His best Test score abroad was at the

Lord’s, when he played as a pure batter and scored 20 and 47, the latter being

the highest score in a total of 110.

Kunderan’s greatest fans would agree that his keeping of wickets was too flashy to be consistent. Of course, he did not suffer in comparison to his supposedly 'superior' peers. He had a tendency to grab, a weakness he never even tried to remedy. If he tried, then he would not have been Budhi. We liked Budhi because he was so unpredictable, so unusual and so individualistic. He was an innocent child in the garb of an adult. We just loved his innocence, his child-like nature.

While discussing unusual incidents on the cricket field, former Test umpire Samar Roy once mentioned to me, “Jaisimha and Kunderan used to chat while taking runs! Against Mike Smith’s MCC at Eden, I remember Budhi, while taking a run, say ‘One, Jai’ and Jai replied ‘Right ho, Buddy’. Mind you, Raju, all this was happening while taking a single in a Test match!”

Only

extraordinary artistes could do so with such spontaneity and casual manner.

What showmanship! They were real entertainers with not a care for the morrow.

I met him just

once. In 1992 at Scotland. I was the coach of Kailash Gattani’s Star Cricket

Club. During the course of a match at Aberdeen I was walking around the ground

where hardly 10 people had gathered to watch. Suddenly I noticed an Indian face

which looked very familiar. Walked up and asked, “Excuse me, are you not Mr Budhi

Kunderan?” The face smiled and nodded. Took me to a boundary-adjacent canopy

for coffee and we conversed and conversed.

When I told him

about his own cricket exploits, his eyes became moist. He was frozen in time. I

mentioned all his unique, non-conventional traits and mannerisms. He was happy,

extremely happy. I realized that he was missing his homeland having married a

British lady and having settled down in UK. He had come to watch his son play

that particular match for the Scottish team.

He expressed no

regrets, no recriminations. Did not criticize, nor did he condemn. He kept all

his frustrations to himself. Whenever I tried to raise a few unsavoury issues,

he said, “Well, that’s life. You win some. You lose some.” When I tried to pay

for the coffee, he took out his wallet and said, “Please let me remain an

Indian. You are in my hometown.”

My last parting

shot actually staggered him. Told him, “In 1964 you snicked John Price and

began to walk before wicket-keeper Binks could even appeal. Then you flung your

bat high in the air and as the bat descended you caught the bat one-handed and

strode away to the pavilion. Never seen such magnificent showmanship on a

cricket field.You should have been on stage or ramp.” Hindustan

Standard had published the picture on the first page.

He ruminated for

a while, “Were you actually there? You saw that happen? You still remember it so

well. I had forgotten the incident. Never quite though about it. Certainly had not

rehearsed it. It was a spontaneous gesture.” Absolutely to the point, he was.

Budhi Kunderan was a spontaneous showman who used the cricket field as his

stage.

Kunderan actually was born 50

years too early. He would have thoroughly enjoyed the slap-bang variety of T20

cricket of today. He would have given tons of thrills and loads of enjoyment to

the spectators.

The modern media with its penchant to highly emphasize characters would have found in him an ideal target. He would have made an ideal model for merchandise with his looks, mannerism and personality.

One particular incident at Eden Gardens I still shudder to relate. Standing on his left toe, Kunderan hooked David Larter and in one reflex action swung his right leg over the stumps! Yes, his heels were just about 2 inches above the bails! I do not think anyone before or since has done such a fascinating act. It was ala Kanhai’s falling sweep. Irresponsible, we thought. But to the irrepressible man it was spontaneous, instinctive A born entertainer, if ever there was one.

Budhi Kunderan was all youth, all adventure, a total non-conformist, a total misfit in Test cricket. But we loved him nevertheless. Akin to his close buddies Durani and Jaisimha, Budhi Kunderan revived the seed of glamour in post-war Indian cricket.

As I got up from my seat and extended my hand, the soulful face uttered, “In life nothing actually adds up. Nothing remains at the end.” I was stunned. Was this Lord Krishna at Kurukshetra or Krishnappa Kunderan in the Scottish Highlands? The sensitivity of Shyamal Mitra’s tune rang in my ears: Jibon khatar proti patay jotoi lekho hishab nikash, kichhui robe na…(In life no matter whatever calculations you make, nothing will remain…).

Is this Budhi,

the baby? Or, Kunderan, the philosopher? He did not extend his hand to clasp

mine. He got up and hugged me! Two totally different personalities, who knew

nothing of each other were locked in an embrace high up at a deserted cricket ground in Aberdeen! Now it was my turn to shed tears…

Different paths

lead to the same goal: thanks to Bhagwan Shri Ramakrishna. The highest

philosophy of Vedanta seeped into me from a most unlikely quarter. Joy

Jagannath. Joy Gopala.