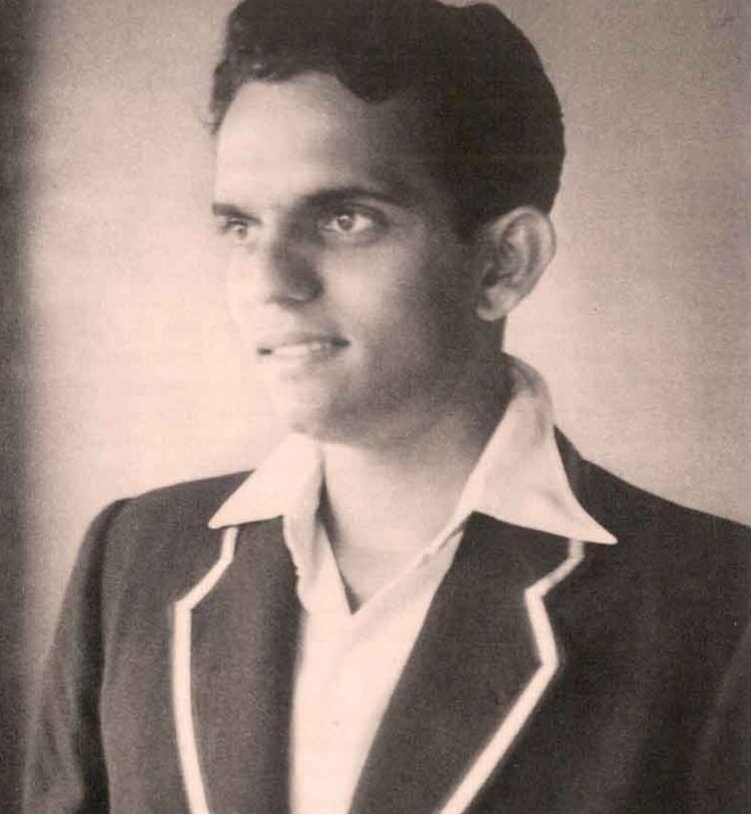

Montu Banerjee in 1948

Unfortunate victims of whimsical selection policy

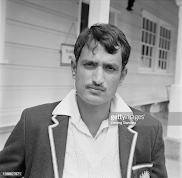

Deepak Shodhan

Deepak Shodhan’s cricket career had a strange resemblance to

that of Madhav Apte’s. They were contemporaries in the Indian cricket of early

1950s. Both made their first appearance in 1952-53 against Pakistan in India.

Both were successful with the willow in hand. Both booked their flight tickets

for the following tour to West Indies in early 1953. In the Caribbean both did

well enough. Enough everyone thought to retain their places. But both were

never heard of again in Test cricket!

Roshan Harshadlal Shodhan (1928-2016) was a middle-order

batter from Gujerat possessing a sound technique and unflappable temperament.

He had the easy elegance of a natural left-hander. At Eden Gardens in the 5th

and last Test against Pakistan, he made his debut for India. Although in the team

as a specialist batter, he was sent to bat as low as number 8. However, he kept

his frustration to himself and decided to make the most of the given

opportunity.

As the 6th wicket fell for 179 runs, the 24 year old, well-built

lad of 6 feet in height walked confidently to the pitch with grim determination.

With characteristic caution he took time to settle down but once he had soaked

in the atmosphere at Eden, he let loose an array of all-round strokes pleasing

to the eye. He looked remarkably matured for a man of his age.

His innings full of responsibility continued till he crossed

his century. The knowledgeable Eden Gardens audience gave him a standing

ovation. He became the first Indian batsman to score a hundred in the first

innings of his first Test match. In the process he helped his team to reach a

respectable total of 397 and to be comfortably placed.

Within months he was on the tour to the Caribbean. In West

Indies in the 1st Test again he went to bat at number 8. He

displayed lovely strokes against wiles of Sonny Ramadhin and company to

register 45 valuable runs. In the 2nd innings he met his first

failure, to be out for 11.

Believe it or not, he was actually dropped from the XI for

the next 3 Tests. No explanations were given. However in the final and 5th

Test again he was selected to play. But this time he was down with an injury

and could not bat in the first innings. In the second knock the injured man

walked in at number 10 and remained unbeaten on 15 as the innings concluded.

Young Deepak Shodhan recovered from his injury. But the

supposedly matured national selectors failed to recover from their mental

block. They seemed to be in some kind of ennui or was it some kind of bias?

The graceful leftie was left high and dry when the next India

team was selected to visit Pakistan in 1954. He was actually omitted in favour

of people who were nowhere near him in talent or in performance. Never was he

invited to represent India again. In the 3 Tests that he played, he had a

century on debut and finished his career with an astounding average of 60.

Again like Madhav Apte, he had a sound academic background

and belonged to a wealthy family which owned mills. Remarkable similarity in destiny

accompanied both the contemporaries. Both stared at sad fate with remarkable

composure. They never complained about the injustice that they had to face.

Even after retirement, neither Apte nor Shodhan was ever

considered to be a selector or in any administrative post. Two former educated

Test cricketers, who owned and ran successful business enterprises, were never

thought to be good enough for cricket administration in India.

Both had the upbringing to discuss subjects apart from

cricket. They were not known for abusive conduct or aggressive behavior on the

field of play. Both were very matured in conduct and in speech. They were

exemplary ambassadors of Indian cricket.

Wonder what really went against them? Was it to do with

cricket? Or, otherwise?

Montu Banerjee

Similar to Shute Banerjee was the destiny of another

Banerjee, Sudhangshu Sekhar (1917-1992). He too played just one Test for India

and he too scalped 5 wickets. Only to find that he was sidelined forever!

Against John Goddard’s West Indies at Eden Gardens in 1948-49

he ‘castled’ both the openers Alan Rae and Denis Atkinson for a mere 28 runs

and went on to capture 2 more wickets in the 1st innings. Added

another one in the next. But all his 5 wickets and 3 catches were instantly

forgotten by the national selectors.

Montu, as he was popularly called, was a fascinating

medium-paced swing bowler with impeccable control. He could swing the ball

either way. With the old ball he could bowl a devastating in-swinger. He was

one of the mainstays of Bengal cricket in the 1940s and 1950s.

Montuda came from a very well-known, highly respected family.

As an arts graduate of the widely-acclaimed Calcutta University of the 1940s,

he had the requisite qualification to be employed in a responsible government

job. By no means did he have to rely on cricket to earn his livelihood.

Nearly six feet in height, and a lithe physique, he had

chiselled features with a broad forehead and a prominent nose. Every inch

revealed a distinct sign of aristocracy. The handsome man moved about in style.

Always dressed in flowing dhoti and silk paanjaabi, he possessed a grand

collection of walking sticks which gave flavour to his distinctive appearance.

Wonder where the fabulous collection is today!

Montuda loved his whisky and his wine but, more importantly,

knew how to nurse those. Magnificent commentator and drinks-connoisseur John

Arlott would have fallen for his company any day. Just as Bhaya – nickname of

the maharaja of Coochbehar and the former Bengal captain – craved for Montuda’s

companionship because the latter had taught his royal-friend to appreciate the

difference between mohua and dheno; between taari and cholai. Bengal

always took pride in its own brand of liquor and prominent personalities were

known to encourage it in the days of the freedom struggle.

When asked about his disappointments in cricket, I could see

the reflection of the legendary Chhobi

Biswas of Jalsha-ghar looking at me with a wry smile, “What disappointment?

I loved the noble game and I still love it. I was an amateur cricketer and am

still proud of being so.”

“But, Montuda, you were certainly not an amateur in your

cricketing skills. You had the brilliant West Indians fumbling to tackle your

aerial movement?”

“That’s for others to judge. Hardly did I care then, nor do I

care now.”

That is just the kind of spirit these exemplary sportsmen

had. Unfortunately they are forgotten souls today.